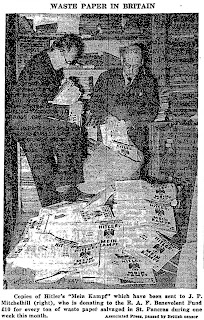

.jpg) The wartime paper shortages were not always without their comedy, as with this image from Britain, which crossed the Atlantic to be published in the New York Times in November 1941. Paper salvage drives were routine across Britain, where "sorters" looked through the great tonnes of books to make sure that nothing considered valuable was lost. It's easy to imagine that this would have been a rather grim business, but equally, not without its chances for comedy. This photograph, for example, is rather cheeky, as the sorters lounge on a pile of copies of Mein Kampf, donated as waste paper. Although not quite a book burning, it's quite clear that the pulping machines have a certain charm. And it's absolutely certain that the machines were considered fascinating: they were often set up in town squares or the like, so that the good burghers could wander past for a look. Bands and speeches were not, of course, considered good form.

The wartime paper shortages were not always without their comedy, as with this image from Britain, which crossed the Atlantic to be published in the New York Times in November 1941. Paper salvage drives were routine across Britain, where "sorters" looked through the great tonnes of books to make sure that nothing considered valuable was lost. It's easy to imagine that this would have been a rather grim business, but equally, not without its chances for comedy. This photograph, for example, is rather cheeky, as the sorters lounge on a pile of copies of Mein Kampf, donated as waste paper. Although not quite a book burning, it's quite clear that the pulping machines have a certain charm. And it's absolutely certain that the machines were considered fascinating: they were often set up in town squares or the like, so that the good burghers could wander past for a look. Bands and speeches were not, of course, considered good form.

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

Paper Salvage: Mein Kampf

.jpg) The wartime paper shortages were not always without their comedy, as with this image from Britain, which crossed the Atlantic to be published in the New York Times in November 1941. Paper salvage drives were routine across Britain, where "sorters" looked through the great tonnes of books to make sure that nothing considered valuable was lost. It's easy to imagine that this would have been a rather grim business, but equally, not without its chances for comedy. This photograph, for example, is rather cheeky, as the sorters lounge on a pile of copies of Mein Kampf, donated as waste paper. Although not quite a book burning, it's quite clear that the pulping machines have a certain charm. And it's absolutely certain that the machines were considered fascinating: they were often set up in town squares or the like, so that the good burghers could wander past for a look. Bands and speeches were not, of course, considered good form.

The wartime paper shortages were not always without their comedy, as with this image from Britain, which crossed the Atlantic to be published in the New York Times in November 1941. Paper salvage drives were routine across Britain, where "sorters" looked through the great tonnes of books to make sure that nothing considered valuable was lost. It's easy to imagine that this would have been a rather grim business, but equally, not without its chances for comedy. This photograph, for example, is rather cheeky, as the sorters lounge on a pile of copies of Mein Kampf, donated as waste paper. Although not quite a book burning, it's quite clear that the pulping machines have a certain charm. And it's absolutely certain that the machines were considered fascinating: they were often set up in town squares or the like, so that the good burghers could wander past for a look. Bands and speeches were not, of course, considered good form.

Friday, July 18, 2008

1933: Paul Tillich

Not many contemporaries actually gave an account of what it was like to attend the 1933 bookfires in Germany. One person who did was the theologian Paul Tillich, who witnessed the fires in Frankfurt am Main. In May 1942, as book burning began to be adopted as one of the standards of Allied propaganda, Tillich took part in a broadcast for the ‘Voice of America’ program (at least, Tillich wrote the piece: the actual broadcast was read out by an actor). The piece, which was broadcast in Germany as well as the United States, is worth quoting at length:

“Many of you still have a picture in your minds of the events of that day. I myself experienced them from a particularly good vantage point and I would like to describe how the scene impressed me. It was in Frankfort on the Main. We stood at a window of the Römer, the ancient building where German emperors were crowned. On the square, which dates back to the Middle Ages, masses of people pushed forward, held back by black and brown shirts. A woodpile was set up. Then we saw a torchlight procession pouring out of the narrow streets, an ending file of students and party men in uniforms. The light of the torches flickered through the darkness and lit up the gables of the houses. I was reminded of paintings of the Spanish Inquisition. Finally, a wheelbarrow or cart drawn by two oxen jolted or stumbled over the cobblestones, laden with books which had been selected for the offering. Behind the wheelbarrow strode the student pastor. When he halted before the stake, he climbed up and stood on top of the wheelbarrow and delivered the damning speech. He threw the first book on the burning woodpile. Hundreds of other books followed. The flames darted upward and lit up the dream picture that was the present. Time had run backward for two hundred years.”

In 1945 Tillich was temporarily blacklisted by the US Army because of his membership in the Council for a Democratic Germany, one of many such coalitions of left-leaning intellectuals set up by German exiles during the war.

“Many of you still have a picture in your minds of the events of that day. I myself experienced them from a particularly good vantage point and I would like to describe how the scene impressed me. It was in Frankfort on the Main. We stood at a window of the Römer, the ancient building where German emperors were crowned. On the square, which dates back to the Middle Ages, masses of people pushed forward, held back by black and brown shirts. A woodpile was set up. Then we saw a torchlight procession pouring out of the narrow streets, an ending file of students and party men in uniforms. The light of the torches flickered through the darkness and lit up the gables of the houses. I was reminded of paintings of the Spanish Inquisition. Finally, a wheelbarrow or cart drawn by two oxen jolted or stumbled over the cobblestones, laden with books which had been selected for the offering. Behind the wheelbarrow strode the student pastor. When he halted before the stake, he climbed up and stood on top of the wheelbarrow and delivered the damning speech. He threw the first book on the burning woodpile. Hundreds of other books followed. The flames darted upward and lit up the dream picture that was the present. Time had run backward for two hundred years.”

In 1945 Tillich was temporarily blacklisted by the US Army because of his membership in the Council for a Democratic Germany, one of many such coalitions of left-leaning intellectuals set up by German exiles during the war.

Monday, July 14, 2008

Burning manuscripts: do the world a good turn

Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673), the Duchess of Newcastle, was a writer and a celebrity, famous for her velvet-clad coachmen and her “hair about her ears”, as a clearly smitten Samuel Pepys noted in his diary (Pepys was one of hundreds who followed her about London, delighted with her extravagance). Pepys was even part of the group who hosted her at the Royal Society, where she admired some flashy experiments. She was immune to most scientific figuring, nonetheless, publishing her wonderful Observations upon Experimental Philosophy in 1666, in which she criticised the new science as the idle hobby of schoolboys. She dismissed, for instance, the new-fangled microscope as an instrument which merely showed the surface of things, rather than their causes. When told that the microscope revealed the common housefly to be the proud owner of hundreds of eyes, Cavendish was appalled: “if two eyes be stronger than a thousand, then nature is to be blamed that she gives such number of eyes to so little a creature.”

She was a poet, an aristocrat, a utopian, and a philosopher. All the more charming that in her Poems, and Fancies (1653), she begins with a brief envoi called ‘The Poetresses hasty Resolution’, in which she is admonished by Reason:

For shame leave off, sayd shee, the Printer spare,

Hee’le loose by your ill Poetry, I feare

Besides the World hath already such a weight

Of uselesse Bookes, as it is over fraught.

Then pitty take, doe the World a good turne,

And all you write cast in the fire, and burne.

Reason, of course, was no match for Cavendish, who dispatched her verse to the Printer with all possible haste.

She was a poet, an aristocrat, a utopian, and a philosopher. All the more charming that in her Poems, and Fancies (1653), she begins with a brief envoi called ‘The Poetresses hasty Resolution’, in which she is admonished by Reason:

For shame leave off, sayd shee, the Printer spare,

Hee’le loose by your ill Poetry, I feare

Besides the World hath already such a weight

Of uselesse Bookes, as it is over fraught.

Then pitty take, doe the World a good turne,

And all you write cast in the fire, and burne.

Reason, of course, was no match for Cavendish, who dispatched her verse to the Printer with all possible haste.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Paper Salvage: has its limits

.jpg)

During the Second World War paper was a much straitened commodity. As a result, paper recycling and salvage drives, around the world but particularly in the United States and to an even greater extent in Great Britain, were commonplace. Among the great swathes of newsprint that were recycled, literally tens of millions of books were also pulped at this time, although most were committed to the machines only after being vetted by volunteers and librarians, who extracted rare and useful items and put them aside, usually donating the salvaged books to libraries, or sending them to POWs. This photograph, which I stumbled across in Life magazine for May 1944, makes an unusual counterpoint, but is also one of very few photos I have ever found of the good guys burning any sort of written material: even confidential papers, as here.

Tuesday, July 8, 2008

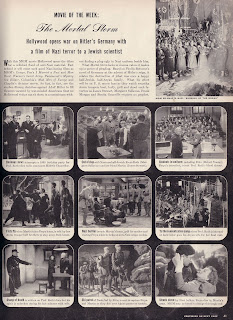

The Mortal Storm

.jpg) A hit for MGM in mid-1940 was the boilover anti-Nazi film The Mortal Storm, starring James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan. It was based on the 1937 novel of the same name by Phyllis Bottome and featured a family of left-leaning assimilated Jewish intellectuals being squeezed out of German society, a position exacerbated when the daughter Freya falls for a sturdy peasant boy with strong Communist beliefs. It's not a bad read, all things considered, but it is the novel's conversion to film that is particularly interesting, because the latter included an influential book burning scene. In the novel, the elderly professor suffers the indignity of having his personal library vetted by stromtroopers, who confiscate a handful of blacklisted works. The scene, that is, shows the insidious effects of censorship extending into the personal home.

A hit for MGM in mid-1940 was the boilover anti-Nazi film The Mortal Storm, starring James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan. It was based on the 1937 novel of the same name by Phyllis Bottome and featured a family of left-leaning assimilated Jewish intellectuals being squeezed out of German society, a position exacerbated when the daughter Freya falls for a sturdy peasant boy with strong Communist beliefs. It's not a bad read, all things considered, but it is the novel's conversion to film that is particularly interesting, because the latter included an influential book burning scene. In the novel, the elderly professor suffers the indignity of having his personal library vetted by stromtroopers, who confiscate a handful of blacklisted works. The scene, that is, shows the insidious effects of censorship extending into the personal home.In the MGM film, however, there's a very different agenda, as this photo-essay from Life makes clear. In an important sequence, the director Frank Borzage pans from the professor having his class disrupted by noisy brown-shirted students, to the scene pictured prominently here, in which uniformed hordes burn books. The scene, which borrows heavily from the original newsreel footage, is probably one of the more accurate recreations of the events, right down to the inclusion of the "fire incantations". In particular, having the scene framed from the perspective of the sympathetic Professor helps shape the response to the meaning of the book burnings: significant, because it was only later in the war years that book burning became one of the most potent symbols of anti-Nazi propaganda.

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Egypt's Culture Minister on "Israeli books"

Playing with metaphors of book burning is still politically fraught, particularly in the Middle East. Recently, Egypt’s Culture Minister Faruq Hosni, a liberal and touted as a candidate to head UNESCO, has drawn fire from writers and diplomats for proclaiming in parliament on 10 May 2008: “I’d burn Israeli books myself if I found any in libraries in Egypt," in reply to questioning from an opposition MP (Hosni, it can be assumed, may not have been aware that this was the 75th anniversary of the original Nazi bookfires in Berlin).

As would be expected of any sure-footed politician, Hosni has since suggested that his remark needs to be put in perspective, but this has not stopped the Simon Wiesenthal Centre writing to UNESCO suggesting that as a “literary pyromaniac” he may not be the man for the top job. Hosni, it's apparent, regrets the remark, and later told AFP that he had merely used “a popular expression to prove something does not exist… A minister of culture cannot demand that a book be burnt, and that includes an Israeli book.”

(There are several reports online; here chiefly from the report published on the European Jewish Press website, written by Alain Navarro, 23 May 2008).

As would be expected of any sure-footed politician, Hosni has since suggested that his remark needs to be put in perspective, but this has not stopped the Simon Wiesenthal Centre writing to UNESCO suggesting that as a “literary pyromaniac” he may not be the man for the top job. Hosni, it's apparent, regrets the remark, and later told AFP that he had merely used “a popular expression to prove something does not exist… A minister of culture cannot demand that a book be burnt, and that includes an Israeli book.”

(There are several reports online; here chiefly from the report published on the European Jewish Press website, written by Alain Navarro, 23 May 2008).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)