Ted Morgan's biography of Somerset Maugham includes this wonderful description of the author making his own decisions about what to preserve from a lifetime of writing:

“He and his secretary, Alan Searle, held a series of ‘bonfire nights’ in the large stone fireplace in the drawing room of the Villa Mauresque in 1958. Piles of letters were thrown in, as well as some of Maugham’s manuscripts. Searle - horrified to see so much valuable material go up in smoke - tried to rescue choice items. Coming down to breakfast after a bonfire night, Maugham would rub his hands and tell Searle: “That was a good night’s work. Now we’ll burn everything you’ve hidden under the sofa.”

Friday, May 30, 2008

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

1933: 'Berlin Savant explains why books were burned'

At the end of 1933, six months after the initial rush of book burnings in Germany, Frederick Schonemann of the University of Berlin spoke at the Chicago council on foreign relations. The crowd was apparently already fractious when someone questioned him from the floor regarding the burning of the books. Schonemann’s reply was salutary: regarding the books burnt, he commented blithely, “a tremendous flood of books on nudism and of a general pornographic nature unfit for either juvenile or adult reading had inundated Germany, and these were burned. I am sorry to say”, he continued, “that the authors of many - of a majority - were Jewish.”

These cheap dismissals were met with more yelling from the crowd, including shouts about the fate of the books of writers such as Helen Keller and Albert Einstein. Schonemann showed he would be swayed neither by emotion nor facts: “No foreign books were burned. I think I am correct in saying that none of Miss Keller’s volumes was included.”

Kathleen McLaughlin, ‘Hecklers shout disapproval of Hitler defender. Berlin Savant explains why books were burned,’ New York Times, 15 November 1933

These cheap dismissals were met with more yelling from the crowd, including shouts about the fate of the books of writers such as Helen Keller and Albert Einstein. Schonemann showed he would be swayed neither by emotion nor facts: “No foreign books were burned. I think I am correct in saying that none of Miss Keller’s volumes was included.”

Kathleen McLaughlin, ‘Hecklers shout disapproval of Hitler defender. Berlin Savant explains why books were burned,’ New York Times, 15 November 1933

Monday, May 26, 2008

Richard Le Gallienne, poet and man of letters

“The whole question of censorship is, of course, difficult, but in view of the contemporary orgy of dirt in literature no one who possesses literary nostrils, so to speak, will deny the need of calling a halt in some way or another. A recourse to the old-fashioned ‘common hangman,’ or to the guillotine, for certain recent books and magazines and their authors and editors as well would, I am sure, gratify many readers who are far from squeamish and would be all to the good of the public health and public decency. Meanwhile the valiant action of Mrs. Bernard Shaw (cited by Mr. Jackson) in burning her copy of Frank Harris’ ‘My Life and Loves,’ “lest the servants should read it,” deserves a wide currency and imitation.”

Richard Le Gallienne, ‘Mr. Jackson on ‘The Fear of Books,’ New York Times, 25 September 1932

Richard Le Gallienne, ‘Mr. Jackson on ‘The Fear of Books,’ New York Times, 25 September 1932

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Burning Textbooks (1907)

In June 1907, on the so-called 'South Field' between W 115th and 116th, Amsterdam and Broadway (New York), the class of 1909 at Columbia held a graduation party. “At 8:30 o’clock the class marched into the field, and the piles of textbooks were brought out in due state. Hal Taylor made the speech, and the books were piled on a kerosene-soaked heap. Then the class of 1909 danced about uttering aboriginal cries that go with such celebrations.” A passing man, the story continues, alerted the fire department. They duly doused the fire, although hampered by some of the students, who tried to make off with the hose.

‘Firemen Douse Students. Columbia Sophomores’ Book-Burning Ceremonies Have Wet Ending,’ New York Times, 1 June 1907, p. 1

Interestingly enough, the South Field is now the square in front of the "Butler Library", which opened in 1934. The Library was named in honour of Nicholas Murray Butler, educator and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, who was a vocal and influential supporter of both attempts to rebuild Louvain University Library after it was burned in 1914 and 1940.

‘Firemen Douse Students. Columbia Sophomores’ Book-Burning Ceremonies Have Wet Ending,’ New York Times, 1 June 1907, p. 1

Interestingly enough, the South Field is now the square in front of the "Butler Library", which opened in 1934. The Library was named in honour of Nicholas Murray Butler, educator and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, who was a vocal and influential supporter of both attempts to rebuild Louvain University Library after it was burned in 1914 and 1940.

Monday, May 19, 2008

Burning Textbooks (1937)

“In place of the age-old custom of burning the books out on the street, which is surrounded by a great deal of shrubbery and foliage, a community sing will be substituted, Daniel Feins, chairman of the numeral lights committee, announced. Feins explained that because of the fire hazard and because of a growing lack of interest in the book-burning celebration, it was to be abandoned this year in favor of a community sing.”

‘City College Lists Busy Finals Week', New York Times, 6 June 1937, p. 49

‘City College Lists Busy Finals Week', New York Times, 6 June 1937, p. 49

Thursday, May 15, 2008

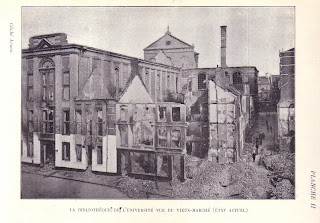

Louvain: The Library of Louvain University, burnt in 1914.

The burning of the University of Louvain in August 1914 was one of the most infamous events of the First World War, and although debate raged over who was responsible (German soldiers, or retreating Allied forces, depending on which side you asked), the Library became a propaganda symbol of the excesses of German "incendiarism". Many books and pamphlets were published denouncing the crime: this image of the burnt-out shell of part of the library is from a small booklet published in 1915 by Paul Delannoy, a professor and librarian at the University of Louvain. His book, L’Université de Louvain: Conferences données au College de France en février 1915 (Paris: 1915) is an anti-German polemic, and he calls the destruction of the library, burnt during the German advance through Belgium in 1914, an "eternal stigma" to German militarism, and hopes that the rebuilding of the library will represent the triumph of "right over force, of civilisation over barbarism".

Monday, May 12, 2008

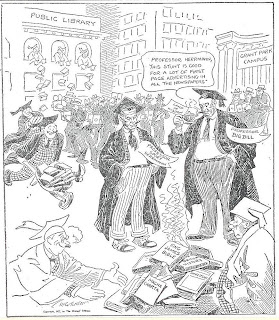

Chicago 1928: "Big Bill" burns "Pro-British" books

.jpg)

1920s Chicago mayor 'Big Bill’ Thompson had been an outspoken critic of American intervention in the First World War (earning him the nickname ‘Kaiser Bill’). During the 1920s his anti-British stance developed to the point that he regularly expressed a standing offer to punch King George ‘on the snoot’ if he ever dared visit Illinois. In 1928 Thompson, acting on a tip-off from the self-styled ‘Patriots’ League’, deputed his friend U.J. ‘Sport’ Herrmann to take four of the most invidious pro-British books to the shores of the lake and torch them. Although it is not even absolutely clear whether the books were eventually destroyed or merely quarantined, Big Bill's posturing was the delight of pundits and cartoonists: here Thompson and his mate Herrmann light their pipes on the 'Lamp of Wisdom'.

Intriguingly, Herrmann was a famed philanthropist, who once lent the same library a quarter of a million dollars. He stayed on the library board after 1928, and became its president in 1933. He is reputed to have told Big Bill that he would help destroy the pro-British books, so long as he wasn't forced to actually read them. Many people have tried to make something of the fact that his yacht was named the 'Swastika', but I will resist.

Paper Salvage: "though the burning of books remains the most perverse gesture", H.D.

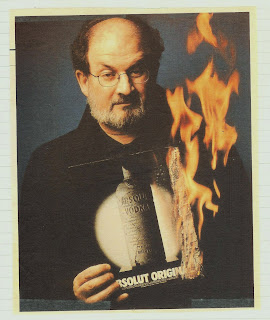

Salman Rushdie & Absolut Vodka

I can't remember where I actually came across this advertisement -- I have a vague memory that it was in the Sydney Morning Herald supplement, the 'Good Weekend', about 4 or 5 years ago. Whatever the case, it's a striking addition to the famous series of Absolut vodka advertisements, showing Rushdie is willing, on occasion, to display a rather cheeky sense of humour about the now infamous fatwa and the burning of The Satanic Verses.

I can't remember where I actually came across this advertisement -- I have a vague memory that it was in the Sydney Morning Herald supplement, the 'Good Weekend', about 4 or 5 years ago. Whatever the case, it's a striking addition to the famous series of Absolut vodka advertisements, showing Rushdie is willing, on occasion, to display a rather cheeky sense of humour about the now infamous fatwa and the burning of The Satanic Verses. "I Commit to the Flames" (1934)

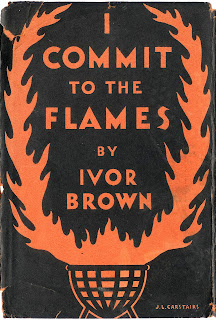

The dustjacket of one of the surprise publishing hits of 1934, theatre critic Ivor Brown's I Commit to the Flames (the title is a direct nod to the so-called Nazi "fire-incantations", the speeches made as books were hurled into bonfires). The book was first published in January, and had gone into a fourth impression by June.

Brown's occasionally funny book includes swipes at all manner of writers, from "Sex-Professors" to T.S. Eliot, from D.H. Lawrence to the music of someone called King Congo. It is all, it would seem, modernity's fault. And the solution? "For some kinds of rubbish the incinerator is the only remedy."

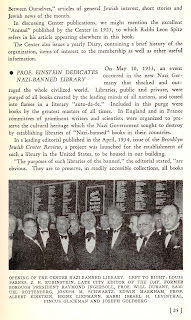

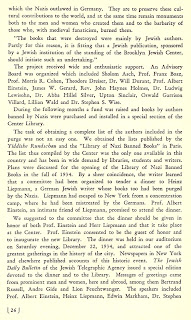

Brooklyn "Nazi-Banned Library" opened by Albert Einstein, December 1934 (from Jubilee Book of the Brooklyn Jewish Center, 1946)

.jpg)

.jpg)

The 'American Library of Nazi Banned Books' was a project of the reformist Brooklyn Jewish Center. It was inaugurated with fanfare before a crowd of 500 guests in December 1934, allowing the organisers plenty of time to prepare for an official opening planned for the second anniversary of the Nazi bookfires in May 1935. It was officially opened by Albert Einstein, who hoped that this American library might snatch some of the banned literary works from oblivion.The Library was openly modelled on the so-called "Library of the Burned Books" in Paris, which had been opened by German exiles in May 1934.

The text of Einstein's speech can be read online; see Einstein Archives Online, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem & the Einstein Papers Project, California Institute of Technology, Nr. 28-293.00.

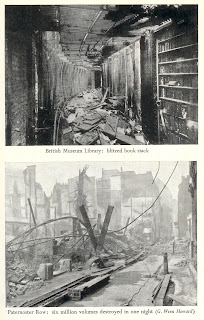

British Museum & Paternoster Row, circa 1940

.jpg) Two amazing photographs of the damage wrought in London by the Blitz. An almost contemporary report on the 'War on Books' commented:

Two amazing photographs of the damage wrought in London by the Blitz. An almost contemporary report on the 'War on Books' commented:“The general public, especially in London, still remembers vividly the big fire raids around St Paul’s when, in Paternoster Row and adjacent streets - the long-established centre of the book trade - more than six million volumes were destroyed. Millions of others have been lost in bookshops and libraries in provincial cities, and millions more in damaged, gutted, or burnt-out warehouses, printing and binding works. A total of twenty million volumes destroyed would probably be an underestimate.”

John Brophy, Britain Needs Books (London: National Book Council, November 1942)

Library of the Burned Books: plaque, Boulevard Arago, Montparnasse, Paris

The former "Library of the Burned Books" (also known as the Deutsche Freiheits Bibliothek), was established in Paris by German and anti-Nazi exiles, and opened on 10 May 1934 (exactly one year after the first major bookfires in Berlin and other German cities). After almost six years as a major research holding, and as a centre for the exiles, it was closed by French authorities during the phoney war. Although the exact fate of the library is not known, it can be assumed that it was destroyed, perhaps burnt, during the first months of the German occupation.

The former "Library of the Burned Books" (also known as the Deutsche Freiheits Bibliothek), was established in Paris by German and anti-Nazi exiles, and opened on 10 May 1934 (exactly one year after the first major bookfires in Berlin and other German cities). After almost six years as a major research holding, and as a centre for the exiles, it was closed by French authorities during the phoney war. Although the exact fate of the library is not known, it can be assumed that it was destroyed, perhaps burnt, during the first months of the German occupation.The Library was in a small studio on the Boulevard Arago in the XIII, not far from the Montparnasse cemetery. From the street there is nothing to commemorate the erstwhile Library (although there are plaques for several of the artists who lived in the precinct). However, in the small foyer, high up above the mailboxes, there is this plaque, with its rather sparse note.

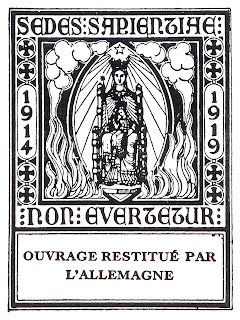

Louvain: Bookplate from Louvain University Library, circa 1930

This bookplate was used in books that were given to the rebuilt Louvain University Library as a result of reparations enforced by the Treaty of Versailles. The Library had been destroyed during the German advance in late August 1914, and a contemporary report commissioned in Germany cleared their army of any wrongdoing (blaming, instead, irregular forces that were alleged to have deployed themselves in and around the library). In the West, the destroyed library became a potent propaganda symbol, and after the war restocking the destroyed library holdings an urgent task. Books and money were donated from around the world, but many more books were taken in the form of reparations from German collections. Hence this bookplate, which shows seated Wisdom rescuing a book from the flames (although a popular misconception thought that the bookplate actually depicted a German soldier setting the halls of the university alight).

This bookplate was used in books that were given to the rebuilt Louvain University Library as a result of reparations enforced by the Treaty of Versailles. The Library had been destroyed during the German advance in late August 1914, and a contemporary report commissioned in Germany cleared their army of any wrongdoing (blaming, instead, irregular forces that were alleged to have deployed themselves in and around the library). In the West, the destroyed library became a potent propaganda symbol, and after the war restocking the destroyed library holdings an urgent task. Books and money were donated from around the world, but many more books were taken in the form of reparations from German collections. Hence this bookplate, which shows seated Wisdom rescuing a book from the flames (although a popular misconception thought that the bookplate actually depicted a German soldier setting the halls of the university alight).Jonathan Rose

"Matthew Fishburn offers an original and often disturbing perspective on a dark chapter in literary history. He has a genius for drawing unexpected connections and he writes with the kind of elegance that was long ago banished from most academic books."

Professor Jonathan Rose, author of The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes and editor of The Holocaust and the Book.

Professor Jonathan Rose, author of The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes and editor of The Holocaust and the Book.

The Book

The Nazi burning of the books in 1933 was one of the most infamous political spectacles of the twentieth century. In Berlin and all over Germany, Nazi officials and students organized elaborate parades and bonfires to mark their embrace of Hitler’s new government. Book burning has since become the symbol of any oppressive regime, and a modern taboo. As Heinrich Heine is often quoted: ‘Where one burns books, one will soon burn people’. This original and provocative new work examines the impact of these fires, concentrating on the years between the Nazi outrages and the publication of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 in 1953, a period in which book burning took hold of the popular imagination. Much more than simply the study of a single shocking event, Burning Books explores how deeply embedded the myths of book burning have become in our cultural and literary history, and illustrates the enduring appeal of a great cleansing bonfire.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

May1943(146).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)